The focal point of the upcoming conference is intellectual engagement. The intellectually engaged student:

Under (well-designed) instruction, students learn how to analyze thinking, assess thinking, and re-construct thinking (improving it thereby). The thinking focused upon is that which is embedded in the content of established academic disciplines. As a result, students so taught become actively engaged in thinking historically, anthropologically, sociologically, politically, chemically, biologically, mathematically, …

Under (well-designed) instruction, students learn how to analyze thinking, assess thinking, and re-construct thinking (improving it thereby). The thinking focused upon is that which is embedded in the content of established academic disciplines. As a result, students so taught become actively engaged in thinking historically, anthropologically, sociologically, politically, chemically, biologically, mathematically, …

The result is that students learn to:

Sessions at the conference will emphasize, among other things,

Sessions at the conference will emphasize, among other things,

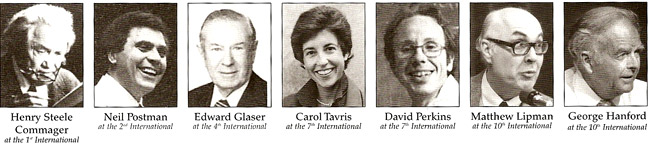

Presenters From Past Conferences

For more than a quarter century, the Foundation for Critical Thinking has emphasized and argued for the importance of teaching for critical thinking in a strong, rather than a weak, sense. We have argued for a clear and “substantive” concept of critical thinking (rather than for one that is ill-defined); for a concept that interfaces well with the disciplines, for a concept that integrates critical with creative thinking, for a concept that applies directly to the needs of everyday and professional life, for a concept that emphasizes the affective as well as the cognitive dimension of critical thinking, for a concept that highlights intellectual standards and traits, for a concept of critical thinking that enables us to organize instruction in every subject area, at every educational level, around it, and on it, and through it.

A substantive concept of critical thinking does not easily reduce to one univocal definition. Rather, it is illuminated by a range of definitions, each highlighting one of its multi-faceted dimensions: its role in intellectual analysis, evaluation, and reconstruction; its role in the array of disciplines (in historical thinking, in anthropological thinking, in sociological thinking, in artistic thinking, in scientific thinking, in the thinking of astronomers and engineers, and so forth); its role in reading, writing, and speaking; its role in investing, doing research, and self-critique; its role in transcending parochialism, egocentrism, and sociocentrism; its role in living a healthy and fit life; its role in civic life; its role in detecting media bias and propaganda; its role in non-partisan, non-ideological ethical reasoning.

One implication of such an emphasis is this: that only through long-term planning can a substantive concept of critical thinking take roots in instruction and learning. Critical thinking cannot be taught per se in any single course, or in any short-period of time. Critical thinking is the key to educational reform and deep learning, but not in any simplistic form and not in any short-term strategy. We need short-term strategies, of course. But without long-term planning nothing substantial occurs, deep learning does not result.

The conference will enable participants to design instruction so that students:

The conference will enable participants to design instruction so that students:

[1] The seven bullets in this section come from the article, THE OXFORD TUTORIAL: ‘Thanks, you taught me how to think’ by David Palfreyman, et.al.