The 28th Annual

International Conference on Critical Thinking Conference Theme:

The Art of Teaching for Intellectual Engagement

July 21-24, 2008 - Preconference July 19-20

“Every Student in Every Class at Every Moment – Intellectually Engaged”

All sessions at the 28th International Conference on Critical Thinking and Education Reform will focus on teaching for intellectual engagement. Conference participants will choose from the sessions below.

The foundations of critical thinking are the focus of the preconference. First time registrants to the conference are strongly encouraged to attend either of the preconference sessions. A grounding in the foundations is essential to making the conference experience a rich one.

| Unlike most academic conferences, the International Conference on Critical Thinking requires intellectual work of all participants in all sessions. One cannot learn critical thinking without doing critical thinking and one cannot do critical thinking without doing intellectual work. Sessions are designed to help you read, write, and think the ideas of critical thinking into your thinking. Active involvement is the key to success at the conference |

THIS EVENT HAS CONCLUDED

Conference Session Title Index (full descriptions below)

Day One: July 21 2008

Participants will choose one from the following selections:

Day Two: July 22 2008

Day Two: July 22 2008 Day Two: Morning Choose one from the following sessions:

Day Two: Afternoon Choose one from the following sessions:

Day Three: July 23 2008

Day Three: Morning (invited concurrent sessions)

Day Three: Morning (invited concurrent sessions)Participants will select from a variety of concurrent sessions at the conference. These sessions focus on contextualization and documentation of critical thinking foundations. All concurrent sessions are invited.

Concurrent Session Schedule

July 23 - Wednesday Morning from 9:00am to 12:00

Day Three: Afternoon Choose one from the following sessions:

Day Four: July 24 2008

Day Four: Morning Choose one from the following sessions:

Day Four: Afternoon

All Participants are invited to attend the closing session, where we will tie all of the sessions together and consider possibilities for moving forward.

Day One: Choose one from the following sessions:

{"id":466,"title":"","author":"","content":"<p><strong><span style=\"font-size: 16pt; color: blue;\">Day One:</span></strong> <span style=\"color: blue;\"><em><span>Choose one from the following sessions:</span></em></span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

A Substantive Approach to Evidence-Based Instruction

“Evidence-Based” instruction is becoming a “buzz concept” in teaching. We must be cautious, however, that our enthusiasm for “evidence-based” instruction does not blind us to the necessity of making instruction and thought “purpose-based, question-based, concept-based, assumption-based, inference-based, and point-of-view-based” as well. Secondly, we must be sensitive to the fact that “evidence” may not in fact be “sound” or “accurate.” In addition, we must be clear about the difference between “evidence,” on the one hand, and “information” on the other. We may think, for example, that we have evidence in hand when we only have information (some of which may be disinformation or misinformation or merely irrelevant information). Information is, undoubtedly, an important element in thinking within any subject or discipline. But it can be, as suggested, accurate or inaccurate, relevant or irrelevant, significant or insignificant, sufficient or insufficient. It can be distorted to fit a particular world view or perspective. It can be misinterpreted as a result of false assumptions, prejudices and biases. In sound evidence-based instruction, the role of information in thinking is carefully conceived and is pedagogically-delivered so as to represent a critical rather than an uncritical use. This session will re-think evidence-based instruction, exploring some of its most important ins and outs.

“Evidence-Based” instruction is becoming a “buzz concept” in teaching. We must be cautious, however, that our enthusiasm for “evidence-based” instruction does not blind us to the necessity of making instruction and thought “purpose-based, question-based, concept-based, assumption-based, inference-based, and point-of-view-based” as well. Secondly, we must be sensitive to the fact that “evidence” may not in fact be “sound” or “accurate.” In addition, we must be clear about the difference between “evidence,” on the one hand, and “information” on the other. We may think, for example, that we have evidence in hand when we only have information (some of which may be disinformation or misinformation or merely irrelevant information). Information is, undoubtedly, an important element in thinking within any subject or discipline. But it can be, as suggested, accurate or inaccurate, relevant or irrelevant, significant or insignificant, sufficient or insufficient. It can be distorted to fit a particular world view or perspective. It can be misinterpreted as a result of false assumptions, prejudices and biases. In sound evidence-based instruction, the role of information in thinking is carefully conceived and is pedagogically-delivered so as to represent a critical rather than an uncritical use. This session will re-think evidence-based instruction, exploring some of its most important ins and outs.

{"id":467,"title":"A Substantive Approach to Evidence-Based Instruction","author":"Richard Paul","content":"<p><img style=\"float: right;\" src=\"https://www.criticalthinking.org/image/pimage/P1010039.jpg\" alt=\"\" />&ldquo;Evidence-Based&rdquo; instruction is becoming a &ldquo;buzz concept&rdquo; in teaching.&nbsp;We must be cautious, however, that our enthusiasm for &ldquo;evidence-based&rdquo; instruction does not blind us to the necessity of making instruction and thought &ldquo;purpose-based, question-based, concept-based, assumption-based, inference-based, and point-of-view-based&rdquo; as well. Secondly, we must be sensitive to the fact that &ldquo;evidence&rdquo; may not in fact be &ldquo;sound&rdquo; or &ldquo;accurate.&rdquo;&nbsp;&nbsp; In addition, we must be clear about the difference between &ldquo;evidence,&rdquo; on the one hand, and &ldquo;information&rdquo; on the other.&nbsp;We may think, for example, that we have <em>evidence</em> in hand when we only have <em>information</em> (some of which may be disinformation or misinformation or merely irrelevant information).&nbsp;Information is, undoubtedly, an important element in thinking within any subject or discipline.&nbsp;But it can be, as suggested, accurate or inaccurate, relevant or irrelevant, significant or insignificant, sufficient or insufficient.&nbsp;It can be distorted to fit a particular world view or perspective.&nbsp;It can be misinterpreted as a result of false assumptions, prejudices and biases.&nbsp;In sound evidence-based instruction, the role of information in thinking is carefully conceived and is pedagogically-delivered so as to represent a <em>critical</em> rather than an <em>uncritical</em> use.&nbsp;This session will re-think evidence-based instruction, exploring some of its most important ins and outs.<br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Engaging Students in Taking Ownership of Content Through Thinking

A key insight into content (and into thinking) is that all content represents a distinctive mode of thinking. Math becomes intelligible as one learns to think mathematically. Biology becomes intelligible as one learns to think biologically. History becomes intelligible as one learns to think historically. This is true because all subjects are: generated by thinking, organized by thinking, analyzed by thinking, synthesized by thinking, expressed by thinking, evaluated by thinking, restructured by thinking, maintained by thinking, transformed by thinking, LEARNED by thinking, UNDERSTOOD by thinking, APPLIED by thinking. If you try to take the thinking out of content, you have nothing, literally nothing, remaining. Learning to think within a unique system of meanings is the key to learning any content whatsoever. This session, in other words, explores the intimate, indeed the inseparable relationship between content and thinking.

{"id":468,"title":"Engaging Students in Taking Ownership of Content Through Thinking","author":"Gerald Nosich","content":"<p><span>A key insight into content (and into thinking) is that all content represents a distinctive mode of thinking. Math becomes intelligible as one learns to <em>think</em> mathematically. Biology becomes intelligible as one learns to <em>think</em> biologically. History becomes intelligible as one learns to <em>think</em> historically. This is true because all subjects are: generated by thinking, organized by thinking, analyzed by thinking, synthesized by thinking, expressed by thinking, evaluated by thinking, restructured by thinking, maintained by thinking, transformed by thinking, LEARNED by thinking, UNDERSTOOD by thinking, APPLIED by thinking. If you try to take the thinking out of content, you have nothing, literally nothing, remaining. Learning to think within a unique system of meanings is the key to learning any <em>content</em> whatsoever. This session, in other words, explores the intimate, indeed the inseparable relationship between content and thinking.<br /> </span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

The Role of Conceptual Analysis in Intellectual Engagement

Ideas are to us like the air we breathe. We project them everywhere. Yet we rarely notice this. We use ideas to create our way of seeing things. What we experience we experience through ideas, often funneled into the categories of “good” and “evil.” We assume ourselves to be good. We assume our enemies to be evil. We select positive terms to cover up the indefensible things we do. We select negative terms to condemn even the good things our enemies do. We conceptualize things personally by means of experience unique to ourselves (often distorting the world to our advantage). We conceptualize things socially as a result of indoctrination or social conditioning (our allegiances presented, of course, in positive terms). Ideas, then, are our paths to both reality and self-delusion. We don’t typically recognize ourselves as engaged in idea construction of any kind whether illuminating or distorting. In our everyday life we don't experience ourselves shaping what we see and constructing the world to our advantage.

Ideas are to us like the air we breathe. We project them everywhere. Yet we rarely notice this. We use ideas to create our way of seeing things. What we experience we experience through ideas, often funneled into the categories of “good” and “evil.” We assume ourselves to be good. We assume our enemies to be evil. We select positive terms to cover up the indefensible things we do. We select negative terms to condemn even the good things our enemies do. We conceptualize things personally by means of experience unique to ourselves (often distorting the world to our advantage). We conceptualize things socially as a result of indoctrination or social conditioning (our allegiances presented, of course, in positive terms). Ideas, then, are our paths to both reality and self-delusion. We don’t typically recognize ourselves as engaged in idea construction of any kind whether illuminating or distorting. In our everyday life we don't experience ourselves shaping what we see and constructing the world to our advantage.

To the uncritical mind, it is as if people in the world came to us with our labels for them inherent in who they are. THEY are “terrorists.” WE are “freedom fighters.” All of us fall victims at times to an inevitable illusion of objectivity. Thus we see others not as like us in a common human nature, but as “friends” and “enemies,” and accordingly “good” or “bad”. Ideology, self-deception, and myth play a large part in our identity and how we think and judge. We apply ideas, however, as if we were simply neutral observers of reality. We often become self-righteous when challenged.

If we want our students to develop as a learners, they must come to recognize the ideas through which they see and experience the world. They must take explicit command of their thinking. They must become the master of their own ideas. Therefore they must become skilled in the art of conceptual analysis. This session will thus focus on the role of conceptual analysis in taking command of one’s mind and one’s life.

{"id":469,"title":"The Role of Conceptual Analysis in Intellectual Engagement","author":"Linda Elder","content":"<p><img style=\"float: right;\" src=\"https://www.criticalthinking.org/image/pimage/P1010073.jpg\" alt=\"\" /><span>Ideas are to us like the air we breathe. We project them everywhere. Yet we rarely notice this. We use ideas to create our way of seeing things. What we experience we experience through ideas, often funneled into the categories of &ldquo;good&rdquo; and &ldquo;evil.&rdquo; We assume ourselves to be good. We assume our enemies to be evil. We select positive terms to cover up the indefensible things we do. We select negative terms to condemn even the good things our enemies do. We conceptualize things personally by means of experience unique to ourselves (often distorting the world to our advantage). We conceptualize things socially as a result of indoctrination or social conditioning (our allegiances presented, of course, in positive terms). Ideas, then, are our paths to both reality and self-delusion. We don&rsquo;t typically recognize ourselves as engaged in idea construction of any kind whether illuminating or distorting. In our everyday life we don't experience ourselves shaping what we see and constructing the world to our advantage.</span><br /> <br /> <span>To the uncritical mind, it is as if people in the world came to us with our labels for them inherent in who they are. THEY are &ldquo;terrorists.&rdquo; WE are &ldquo;freedom fighters.&rdquo; All of us fall victims at times to an inevitable illusion of objectivity. Thus we see others not as like us in a common human nature, but as &ldquo;friends&rdquo; and &ldquo;enemies,&rdquo; and accordingly &ldquo;good&rdquo; or &ldquo;bad&rdquo;. Ideology, self-deception, and myth play a large part in our identity and how we think and judge. We apply ideas, however, as if we were simply neutral observers of reality. We often become self-righteous when challenged.</span> <br /> <br /> <span>If we want our students to develop as a learners, they must come to recognize the ideas through which they see and experience the world. They must take explicit command of their thinking. They must become the master of their own ideas. Therefore they must become skilled in the art of conceptual analysis.&nbsp;This session will thus focus on the role of conceptual analysis in taking command of one&rsquo;s mind and one&rsquo;s life.</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Fostering Critical Thinking in the High School Classroom

Bringing critical thinking into the high school classroom entails understanding the concepts and principles embedded in critical thinking and then applying those concepts throughout the curriculum. It means developing powerful strategies that emerge when we begin to understand critical thinking. In this session we will focus on strategies for engaging the intellect at the high school level. These strategies are powerful and useful, because each is a way to get students actively engaged in thinking about what they are trying to learn. Each represents a shift of responsibility for learning from the teacher to the student. These strategies suggest ways to get your students to do the hard work of learning.

{"id":470,"title":"Fostering Critical Thinking in the High School Classroom","author":"Enoch Hale","content":"<p><span>Bringing critical thinking into the high school classroom entails understanding the concepts and principles embedded in critical thinking and then applying those concepts throughout the curriculum.&nbsp;&nbsp; It means developing powerful strategies that emerge when we begin to understand critical thinking. In this session we will focus on strategies for engaging the intellect at the high school level.&nbsp;These strategies are powerful and useful, because each is a way to get students actively engaged in thinking about what they are try&shy;ing to learn. Each represents a shift of responsibility for learning from the teacher to the student. These strategies suggest ways to get your students to do the hard work of learning.</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Advanced Session: In Search of a History of Critical Thinking: Greece to the Renaissance

(500 B.C.E. to 1400 C.E.) The first of five sessions on the history of Critical Thinking

(500 B.C.E. to 1400 C.E.) The first of five sessions on the history of Critical Thinking

The intellectual roots of critical thinking are ancient, traceable to at least 500 B.C. in the writings of some Greek thinkers in some Greek city states. There were some conditions conducive to that development of critical thinking. For example, because most Greeks were polytheistic, they were highly tolerant of divergent religious beliefs. The emergence of democracy in some Greek city states was conducive to civic debate and argumentation. We will examine the degree of freedom of thought implicit in the writings of some thinkers before Socrates and some after, including not only Plato and Aristotle, and some Skeptics, Stoics, and Epicureans, but also such thinkers as Cicero, Seneca, Polybius, and Plotinus. (to 500 A.D.) Our interest will not be in their philosophies per se, but in the degree to which they exemplified, individually and collectively, some degree or dimensions of critical thought, as well as the extent to which their writings reflected the social conditions of the time. The period of time from the dark ages through the medieval era to the Renaissance (400-1400.) will principally be a study in intolerance and persecution of those who displayed any tendency to dissent from the received orthodox thinking. The history of the Inquisition and related social forces and conditions will be highlighted. Feudal society, in turn, will be analyzed as paradigm conditions for the suppression of freedom of thought, and hence of critical thought.

{"id":471,"title":"Advanced Session: In Search of a History of Critical Thinking: Greece to the Renaissance","author":"Rush Cosgrove","content":"<p><img style=\"float: right;\" src=\"https://www.criticalthinking.org/image/pimage/P1010120.jpg\" alt=\"\" /><span class=\"f2\"><strong>(500 B.C.E. to 1400 C.E.) </strong><span style=\"color: #000080;\"><strong>The first of five sessions on the history of Critical Thinking</strong></span> <br /> <span>The intellectual roots of critical thinking are ancient, traceable to at least 500 B.C. in the writings of some Greek thinkers in some Greek city states.&nbsp;There were some conditions conducive to that development of critical thinking.&nbsp;For example, because most Greeks were polytheistic, they were highly tolerant of divergent religious beliefs.&nbsp; The emergence of democracy in some Greek city states was conducive to civic debate and argumentation.&nbsp;We will examine the degree of freedom of thought implicit in the writings of some thinkers before Socrates&nbsp;and some after, including not only Plato and Aristotle, and some Skeptics, Stoics, and Epicureans, but also such thinkers as Cicero, Seneca, Polybius, and Plotinus. (to 500 A.D.) Our interest will not be in their philosophies per se, but in the degree to which they exemplified, individually and collectively, some degree or dimensions of critical thought, as well as the extent to which their writings reflected the social conditions of the time.&nbsp;The period of time from the dark ages through the medieval era to the Renaissance (400-1400.) will principally be a study in intolerance and persecution of those who displayed any tendency to dissent from the received orthodox thinking.&nbsp;The history of the Inquisition and related social forces and conditions will be highlighted. Feudal society, in turn, will be analyzed as paradigm conditions for the suppression of freedom of thought, and hence of critical thought. </span></span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Day Two: Morning Choose one from the following sessions:

{"id":472,"title":"","author":"","content":"<p><strong><span style=\"font-size: 16pt; color: blue;\">Day Two: Morning </span></strong><span style=\"color: blue;\"><em><span>Choose one from the following sessions:</span></em></span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Teaching Students to Ask Essential Questions

It is not possible to be a good thinker and a poor questioner. Questions define tasks, express problems, and delineate issues. They drive thinking forward. Answers, on the other hand, often signal a full stop in thought. Only when an answer generates further questions does thought continue as inquiry. A mind with no questions is a mind that is not intellectually alive. No questions (asked) equals no understanding (achieved). Superficial questions equal superficial understanding, unclear questions equal unclear understanding. If your mind is not actively generating questions, you are not engaged in substantive learning. So the question is raised, “How can we teach so that students generate questions that lead to deep learning?” In this session we shall focus on practical strategies for generating questioning minds---at the same time, of course, that students learn the content that is at the heart of the curriculum.

{"id":473,"title":"Teaching Students to Ask Essential Questions","author":"Richard Paul","content":"<p><span>It is not possible to be a good thinker and a poor questioner. Questions define tasks, express problems, and delineate issues. They drive thinking forward. Answers, on the other hand, often signal a full stop in thought. Only when an answer generates further questions does thought continue as inquiry. A mind with no questions is a mind that is not intellectually alive. No questions (asked) equals no understanding (achieved). Superficial questions equal superficial understanding, unclear questions equal unclear understanding. If your mind is not actively generating questions, you are not engaged in substantive learning. So the question is raised, &ldquo;How can we teach so that students generate questions that lead to deep learning?&rdquo; In this session we shall focus on practical strategies for generating questioning minds---at the same time, of course, that students learn the content that is at the heart of the curriculum.</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

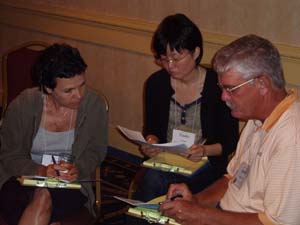

The Role of Intellectual Traits and Dispositions in Engaging the Intellect

Critical thinking is not just a set of intellectual skills. It is a way of orienting oneself in the world. It is a way of approaching problems that differs significantly from that which is typical in human life. People may have critical thinking skills and abilities, and yet still be unable to enter viewpoints with which they disagree. They may have critical thinking abilities, and yet still be unable to analyze the beliefs that guide their behavior. They may have critical thinking abilities, and yet be unable to distinguish between what they know and what they don’t know, to persevere through difficult problems and issues, to think fairmindedly, to stand alone against the crowd. This session focuses on designing instruction that transforms the mind, instruction that fosters the development of fairmindedness, intellectual humility, intellectual perseverance, intellectual courage, intellectual empathy, intellectual autonomy, intellectual integrity, and confidence in reason.

Critical thinking is not just a set of intellectual skills. It is a way of orienting oneself in the world. It is a way of approaching problems that differs significantly from that which is typical in human life. People may have critical thinking skills and abilities, and yet still be unable to enter viewpoints with which they disagree. They may have critical thinking abilities, and yet still be unable to analyze the beliefs that guide their behavior. They may have critical thinking abilities, and yet be unable to distinguish between what they know and what they don’t know, to persevere through difficult problems and issues, to think fairmindedly, to stand alone against the crowd. This session focuses on designing instruction that transforms the mind, instruction that fosters the development of fairmindedness, intellectual humility, intellectual perseverance, intellectual courage, intellectual empathy, intellectual autonomy, intellectual integrity, and confidence in reason.

{"id":474,"title":"The Role of Intellectual Traits and Dispositions in Engaging the Intellect","author":"Linda Elder","content":"<p><img style=\"float: right;\" src=\"https://www.criticalthinking.org/image/pimage/P1010010.jpg\" alt=\"\" /><span>Critical thinking is not just a set of intellectual skills. It is a way of orienting oneself in the world. It is a way of approaching problems that differs significantly from that which is typical in human life. People may have critical thinking skills and abilities, and yet still be unable to enter viewpoints with which they disagree. They may have critical thinking abilities, and yet still be unable to analyze the beliefs that guide their behavior. They may have critical thinking abilities, and yet be unable to distinguish between what they know and what they don&rsquo;t know, to persevere through difficult problems and issues, to think fairmindedly, to stand alone against the crowd. This session focuses on designing instruction that transforms the mind, instruction that fosters the development of fairmindedness, intellectual humility, intellectual perseverance, intellectual courage, intellectual empathy, intellectual autonomy, intellectual integrity, and confidence in reason.</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Fostering Intellectual Engagement through Critical Reading

Educated persons are skilled at and routinely engage in close reading and substantive writing. Through the ability to read closely, to comprehend and apply what one reads, students can master a subject from books alone, without benefit of lectures or class discussion. Indeed, through well-developed reading abilities, it is possible to become educated through reading alone. Skilled readers do this through intellectually interacting with the author as they read. They actively question as they read. They seek to deeply understand what they read. They make connects as they read. They evaluate as they read. They bring important ideas into their thinking as they read. This session will explore ways and means for developing student skills in close reading.

{"id":475,"title":"Fostering Intellectual Engagement through Critical Reading","author":"Enoch Hale","content":"<p><span>Educated persons are skilled at and routinely engage in close reading and substantive writing. Through the ability to read closely, to comprehend and apply what one reads, students can master a subject from books alone, without benefit of lectures or class discussion. Indeed, through well-developed reading abilities, it is possible to become educated through reading alone. Skilled readers do this through intellectually interacting with the author as they read. They actively question as they read. They seek to deeply understand what they read. They make connects as they read. They evaluate as they read. They bring important ideas into their thinking as they read. This session will explore ways and means for developing student skills in close reading.</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Embedding Core Concepts in Instruction

Concepts are tools we use in thinking. They enable us to group things in our experience in different categories, classes, or divisions. They are the labels we apply to things in our minds. They represent the mental map (and meanings) we construct of the world, the map that tells us the way the world is. Through our concepts we define situations, events, relationships, and all other objects of our experience. All of our decisions depend on how we conceptualize the world. Each subject gives us a unique vocabulary of concepts to use in thinking within the field that the discipline represents.

Concepts are tools we use in thinking. They enable us to group things in our experience in different categories, classes, or divisions. They are the labels we apply to things in our minds. They represent the mental map (and meanings) we construct of the world, the map that tells us the way the world is. Through our concepts we define situations, events, relationships, and all other objects of our experience. All of our decisions depend on how we conceptualize the world. Each subject gives us a unique vocabulary of concepts to use in thinking within the field that the discipline represents.

All subjects or disciplines are defined by their foundational concepts. When students master concepts at a deep level, they are able to use them to understand and function better within the world. Can you identify the fundamental concepts in every subject you teach or study? Can you explain their role in thinking within your discipline? Can you help students take command of core concepts? These are some of the questions we will explore in this session.

{"id":476,"title":"Embedding Core Concepts in Instruction","author":"Gerald Nosich","content":"<p><img style=\"float: right;\" src=\"https://www.criticalthinking.org/image/pimage/P1010042.jpg\" alt=\"\" /><span>Concepts are tools we use in thinking. They enable us to group things in our experience in different categories, classes, or divisions. They are the labels we apply to things in our minds. They represent the mental map (and meanings) we construct of the world, the map that tells us the way the world is. Through our concepts we define situations, events, relationships, and all other objects of our experience. All of our decisions depend on how we conceptualize the world. Each subject gives us a unique vocabulary of concepts to use in thinking within the field that the discipline represents. </span><br /> <br /> <span>All subjects or disciplines are defined by their foundational concepts. When students master concepts at a deep level, they are able to use them to understand and function better within the world. Can you identify the fundamental concepts in every subject you teach or study? Can you explain their role in thinking within your discipline? Can you help students take command of core concepts? These are some of the questions we will explore in this session.</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

**Advanced Session: In Search of a History of Critical Thinking: The Renaissance (1400-1600 C.E.)

The Struggle for Freedom of Thought Surfaces Against Powerful Forces for Religious and Political Intolerance.

Some relevant thinkers to be explored in this session: Colet, Eramus, More, Bacon, Machiavelli

{"id":477,"title":"**Advanced Session: In Search of a History of Critical Thinking: The Renaissance (1400-1600 C.E.)","author":"Rush Cosgrove","content":"<p><span>The Struggle for Freedom of Thought Surfaces Against Powerful Forces for Religious and Political Intolerance.</span> <br /> <br /> Some relevant thinkers to be explored in this session:&nbsp;Colet, Eramus, More, Bacon, Machiavelli<br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Infusing Critical Thinking into Elementary Instruction: Part One

This session will provide teachers with strategies for fostering critical thinking at the elementary level. Special emphasis will be placed on helping students understand what it means to be a fair-minded critical thinker and how they can achieve this goal by learning to take their thinking apart, evaluate it and then improve it. To this end, Drs. Borman and Levine will focus on strategies for teaching elementary students the Elements of Thinking and the Universal Intellectual Standards and how to use these conceptual sets to evaluate and improve thinking. Participants will develop learning activities designed to foster critical thinking.

{"id":478,"title":"Infusing Critical Thinking into Elementary Instruction: Part One","author":"Suzanne Borman and Joel Levine","content":"<p><span>This session will provide teachers with strategies for fostering critical thinking at the elementary level.&nbsp;Special emphasis will be placed on helping students understand what it means to be a fair-minded critical thinker and how they can achieve this goal by learning to take their thinking apart, evaluate it and then improve it.&nbsp;To this end, Drs. Borman and Levine will focus on strategies for teaching elementary students the Elements of Thinking and the Universal Intellectual Standards and how to use these conceptual sets to evaluate and improve thinking.&nbsp;Participants will develop learning activities designed to foster critical thinking.</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Day Two: Afternoon Choose one from the following sessions:

{"id":479,"title":"","author":"","content":"<p><strong><span style=\"font-size: 16pt; color: blue;\">Day Two: Afternoon </span></strong><span style=\"color: blue;\"><em><span>Choose one from the following sessions:</span></em></span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Fostering Multilogical Thinking Within the Disciplines

In some disciplines, the experts rarely disagree; in others, disagreement is common. The reason for this is found in the kinds of questions they ask and the nature of what they study. Mathematics and the physical and biological sciences fall into the first category. They study phenomena that behave consistently under predictable conditions and they pose questions that can be expressed clearly and precisely, with virtually complete expert

In some disciplines, the experts rarely disagree; in others, disagreement is common. The reason for this is found in the kinds of questions they ask and the nature of what they study. Mathematics and the physical and biological sciences fall into the first category. They study phenomena that behave consistently under predictable conditions and they pose questions that can be expressed clearly and precisely, with virtually complete expert

agreement. The disciplines dealing with humans, in contrast—all the social disciplines, the Arts, and the Humanities—fall into the second category. What they study is often unpredictably variable.

For example, humans are born into a culture at some point in time in some place, raised by parents with particular beliefs, and form a variety of associations with other humans who are equally variously influenced. What is dominant in our behavior varies from person to person. Hence, many of the questions asked in the disciplines dealing with human nature are subject to disagreement among experts (who approach the questions from different points of view).

Consider the varieties of ways that human minds are influenced:

- sociologically (our minds are influenced by the social groups to which we belong);

- philosophically (our minds are influenced by our personal philosophy);

- ethically (our minds are influenced by our ethical character);

- intellectually (our minds are influenced by the ideas we hold, by the manner in which we reason and deal with abstractions);

- anthropologically (our minds are influenced by cultural practices, mores, and taboos);

- ideologically and politically (our minds are influenced by the structure of power and its use by interest groups around us);

- economically (our minds are influenced by the economic conditions under which we live);

- historically (our minds are influenced by our history and by the way we tell our history);

- biologically (our minds are influenced by our biology and neurology);

- theologically (our minds are influenced by our religious beliefs); and,

- psychologically (our minds are influenced by our personality and egocentric tendencies).

This session, then, will focus on helping students learn to reason through multilogical problems and issues within the disciplines. Participants will formulate multilogical questions within their disciplines and consider how skilled thinkers from different perspectives would reason through those questions. Participants will also think through how to engage students in the same process.

{"id":480,"title":"Fostering Multilogical Thinking Within the Disciplines","author":"Linda Elder","content":"<p><img id=\"__mce\" style=\"float: right;\" src=\"https://www.criticalthinking.org/image/pimage/P1010063.jpg\" alt=\"\" /><span>In some disciplines, the experts rarely disagree; in others, disagreement is common. The reason for this is found in the kinds of questions they ask and the nature of what they study. Mathematics and the physical and biological sciences fall into the first category. They study phenomena that behave consistently under predictable conditions and they pose questions that can be expressed clearly and precisely, with virtually complete expert</span></p>\r\n<p><span>agreement. The disciplines dealing with humans, in contrast&mdash;all the social disciplines, the Arts, and the Humanities&mdash;fall into the second category. What they study is often unpredictably variable. </span></p>\r\n<p><span>For example, humans are born into a culture at some point in time in some place, raised by parents with particular beliefs, and form a variety of associations with other humans who are equally variously influenced. What is dominant in our behavior varies from person to person. Hence, many of the questions asked in the disciplines dealing with human nature are subject to disagreement among experts (who approach the questions from different points of view). </span></p>\r\n<p><span>Consider the varieties of ways that human minds are influenced:</span></p>\r\n<ul>\r\n<li><span><strong>sociologically </strong>(our minds are influenced by the social groups to which we belong);</span></li>\r\n<li><strong>philosophically </strong>(our minds are influenced by our personal philosophy);</li>\r\n<li><strong>ethically </strong>(our minds are influenced by our ethical character);</li>\r\n<li><strong>intellectually </strong>(our minds are influenced by the ideas we hold, by the manner in which we reason and deal with abstractions);</li>\r\n<li><strong>anthropologically </strong>(our minds are influenced by cultural practices, mores, and taboos);</li>\r\n<li><strong>ideologically and politically </strong>(our minds are influenced by the structure of power and its use by interest groups around us);</li>\r\n<li><strong>economically </strong>(our minds are influenced by the economic conditions under which we live);</li>\r\n<li><strong>historically </strong>(our minds are influenced by our history and by the way we tell our history);</li>\r\n<li><strong>biologically </strong>(our minds are influenced by our biology and neurology);</li>\r\n<li><strong>theologically </strong>(our minds are influenced by our religious beliefs); and,<span>&nbsp;</span></li>\r\n<li><span><strong>psychologically </strong>(our minds are influenced by our personality and egocentric tendencies).</span></li>\r\n</ul>\r\n<div><span>This session, then, will focus on helping students learn to reason through multilogical problems and issues within the disciplines.&nbsp;Participants will formulate multilogical questions within their disciplines and consider how skilled thinkers from different perspectives would reason through those questions.&nbsp;Participants will also think through how to engage students in the same process.</span></div>\r\n<p><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Role of Administration in Building a Community of Intellectually Engaged Faculty, Students and Staff

Critical thinking, deeply understood, provides a rich set of concepts that enable us to think our way through any subject or discipline, through any problem or issue. With a substantive concept of critical thinking clearly in mind, we begin to see the pressing need for a staff development program that fosters critical thinking within and across the curriculum. As we come to understand a substantive concept of critical thinking, we are able to follow-out its implications in designing a professional development program. By means of it, we begin to see important implications for every part of the institution –redesigning policies, providing administrative support for critical thinking, rethinking the mission, coordinating and providing faculty workshops in critical thinking, redefining faculty as learners as well as teachers, assessing students, faculty, and the institution as a whole in terms of critical thinking abilities and traits. We realize that robust critical thinking should be the guiding force for all of our educational efforts. This session presents a professional development model that can provide the vehicle for deep change across the curriculum, across the institution.

{"id":481,"title":"Role of Administration in Building a Community of Intellectually Engaged Faculty, Students and Staff","author":"Gerald Nosich","content":"<p><span>Critical thinking, deeply understood, provides a rich set of concepts that enable us to think our way through any subject or discipline, through any problem or issue. With a substantive concept of critical thinking clearly in mind, we begin to see the pressing need for a staff development program that fosters critical thinking within and across the curriculum. As we come to understand a substantive concept of critical thinking, we are able to follow-out its implications in designing a professional development program. By means of it, we begin to see important implications for every part of the institution &ndash;redesigning policies, providing administrative support for critical thinking, rethinking the mission, coordinating and providing faculty workshops in critical thinking, redefining faculty as learners as well as teachers, assessing students, faculty, and the institution as a whole in terms of critical thinking abilities and traits. We realize that robust critical thinking should be the guiding force for all of our educational efforts.&nbsp;This session presents a professional development model that can provide the vehicle for deep change across the curriculum, across the institution.</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

How to Avoid the Trap of Education Fads

The history of schooling is also the history of educational panaceas, the comings and goings of quick-fixes for deep-seated educational problems. This old problem is not being reduced. Rather, it is dramatically on the increase. This results in intensifying fragmentation of energy and effort in the schools - together with a significant waste of time and money. Many teachers become increasingly cynical and jaded.

The history of schooling is also the history of educational panaceas, the comings and goings of quick-fixes for deep-seated educational problems. This old problem is not being reduced. Rather, it is dramatically on the increase. This results in intensifying fragmentation of energy and effort in the schools - together with a significant waste of time and money. Many teachers become increasingly cynical and jaded.

It is time to recognize that education will never be improved by simplistic educational fads. Fads by their nature are fated to self-destruction. Teachers and administrators need to understand the problem of educational fads so that they can effectively distinguish substantive efforts at educational reform from superficial ones.

All educational trends or fads have their roots in reasonable ideas. Trends become fads when a reasonable idea is applied unreasonably. All reasonable ideas enhance education when integrated into a substantive concept of education. They fail when imposed upon instruction through a non-substantive, fragmented, conception of education. In this session, we focus on some of the current educational trends or fads in schooling today.

{"id":482,"title":"How to Avoid the Trap of Education Fads","author":"Richard Paul","content":"<p><img style=\"float: right;\" src=\"https://www.criticalthinking.org/image/pimage/PPL1010115.jpg\" alt=\"\" /><span>The history of schooling is also the history of educational panaceas, the comings and goings of quick-fixes for deep-seated educational problems. This old problem is not being reduced. Rather, it is dramatically on the increase. This results in intensifying fragmentation of energy and effort in the schools - together with a significant waste of time and money. Many teachers become increasingly cynical and jaded. </span><br /> <br /> <span>It is time to recognize that education will never be improved by simplistic educational fads. Fads by their nature are fated to self-destruction. Teachers and administrators need to understand the problem of educational fads so that they can effectively distinguish substantive efforts at educational reform from superficial ones. </span><br /> <br /> <span>All educational trends or fads have their roots in reasonable ideas. Trends become fads when a reasonable idea is applied unreasonably. All reasonable ideas enhance education when integrated into a substantive concept of education. They fail when imposed upon instruction through a non-substantive, fragmented, conception of education. In this session, we focus on some of the current educational trends or fads in schooling today.</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

**Advanced Session: In Search of a History of Critical Thinking:

Science and The Age of Revolution (1600 to 1850)

Rush Cosgrove

The Growing Power of Nationalism, Imperialism, and Colonialism : The Theory of Human Rights in Conflict with the Imposition of Hegemony of European Nations Over Less Technologically Developed Cultures (in the Americas, Africa, and the Orient).

Some relevant thinkers: Bacon, Hobbes, Galileo, Descartes, Locke, Tom Paine, Voltaire, Condillac.

{"id":483,"title":"**Advanced Session: In Search of a History of Critical Thinking:","author":"","content":"<p><strong class=\"head\">Science and The Age of Revolution (1600 to 1850)<br /> </strong><span class=\"f2\">&nbsp;&nbsp; <strong>Rush Cosgrove</strong> </span><br /> <span>The Growing Power of Nationalism, Imperialism,&nbsp;and Colonialism&nbsp;: The Theory of Human Rights in Conflict with the Imposition of&nbsp;Hegemony of European Nations Over Less Technologically Developed Cultures (in the Americas, Africa, and the Orient).</span><br /> <br /> <span>Some relevant thinkers: Bacon, Hobbes, Galileo, Descartes, Locke, Tom Paine, Voltaire, Condillac.</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Infusing Critical Thinking into Elementary Instruction: Part Two

Building on the foundational concepts covered in the first session, this session will continue to focus on infusing critical thinking in elementary instruction throughout the curriculum and within student relationships. Participants will be engaged in applying the elements of reasoning and intellectual standards within content areas including math, language arts, and social studies. Classroom management issues will also be addressed through application of critical thinking strategies.

{"id":484,"title":"Infusing Critical Thinking into Elementary Instruction: Part Two","author":"Suzanne Borman and Joel Levine","content":"<p><span>Building on the foundational concepts covered in the first session, this session will continue to focus on infusing critical thinking in elementary instruction throughout the curriculum and within student relationships.&nbsp;Participants will be engaged in applying the elements of reasoning and intellectual standards within content areas including math, language arts, and social studies.&nbsp;Classroom management issues will also be addressed through application of critical thinking strategies.</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Day Three: Morning Invited Concurrent sessions:

Participants will select from concurrent sessions at the conference. These sessions focus on contextualization and documentation of critical thinking foundations. All concurrent sessions are invited.

Concurrent Session Schedule

{"id":485,"title":"","author":"","content":"<p><strong id=\"__mce\"><span style=\"font-size: 16pt; color: blue;\">Day Three: Morning </span></strong><span style=\"color: blue;\"><em><span>Invited Concurrent sessions:<br /> </span></em></span> Participants will select from concurrent sessions at the conference.&nbsp; These sessions focus on contextualization and documentation of critical thinking foundations.&nbsp; All concurrent sessions are invited.<br /> <br /></p>\r\n<p><span><strong><span style=\"color: #000080;\">Concurrent Session Schedule</span></strong><br /> </span></p>\r\n<p><span> </span></p>\r\n<ul>\r\n<li><a href=\"/files/Concurrent%20Program.doc\" target=\"_blank\">Concurrent Sessions (Word Doc)</a> </li>\r\n<li><a href=\"/files/Concurrent%20Program.pdf\" target=\"_blank\">Concurrent Sessions (Acrobat PDF)</a></li>\r\n</ul>\r\n<p><span> </span></p>\r\n<p>&nbsp;</p>\r\n<p><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Day Three: Afternoon Choose from one of the following sessions:

{"id":486,"title":"","author":"","content":"<p><strong><span style=\"font-size: 16pt; color: blue;\">Day Three: Afternoon </span></strong><span style=\"color: blue;\"><em><span>Choose from one of the following sessions:</span></em></span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Understanding Egocentric Pathologies That Impede Intellectual Development

To reason well, we must understand, not only how to take our thinking apart and assess it, not only, in other words, the tools and concepts that critical thinking offers, but also the powerful barriers, that exist naturally in the mind, to good reasoning. This session will target some of those barriers. We will focus, for example, on self-deception, bias, prejudice, distortion of information and ideas, intellectual arrogance, intellectual hypocrisy, narrow-mindedness, and stereotyping. We will offer a theory of mind which can help you, and your students, become more aware of the native egocentric tendencies that operate in the mind and that keep you from reaching your potential as thinker.

{"id":487,"title":"Understanding Egocentric Pathologies That Impede Intellectual Development","author":"Linda Elder","content":"<p><span>To reason well, we must understand, not only how to take our thinking apart and assess it, not only, in other words, the tools and concepts that critical thinking offers, but also the powerful barriers, that exist naturally in the mind, to good reasoning.&nbsp;This session will target some of those barriers.&nbsp;We will focus, for example, on self-deception, bias, prejudice, distortion of information and ideas, intellectual arrogance, intellectual hypocrisy, narrow-mindedness, and stereotyping.&nbsp;We will offer a theory of mind which can help you, and your students, become more aware of the native egocentric tendencies that operate in the mind and that keep you from reaching your potential as thinker.</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Advanced Session: Paul and His Critics

Clarifying the Discourse on Critical Thinking: Where and How Paul Provides the Framework for a Trans-Disciplinary Conceptualization:

Clarifying the Discourse on Critical Thinking: Where and How Paul Provides the Framework for a Trans-Disciplinary Conceptualization:

It is widely agreed that the discourse on critical thinking is fragmented. Although common conceptualizations can be found in the numerous definitions of critical thinking, this base-line is often abandoned in lieu of discipline specific conceptualizations that do little to challenge the status quo both in departmental traditions and in its applications within education. Since critical thinking provides the tools for analyzing and assessing thinking within every subject and discipline, and thus without these tools, no subjects or disciplines can exist, it follows that critical thinking must be placed at the heart of the curriculum within and across the disciplines. Paul has developed a trans-disciplinary approach to critical thinking that explicitly illuminates the link between critical thinking and thinking within the disciplines. He has shaped a concept of critical thinking with substance and vision, applicable to every domain of human thought.

This session will examine Paul's work in relation to the rather fragmented discourse on critical thinking. It will outline Paul's mission and critics, and it will critique the different ways scholars have constructed discipline specific conceptualizations of critical thinking. The purpose, then, is to clarify the discourse and Paul's place within it for those interested in the theory of critical thinking.

{"id":488,"title":"Advanced Session: Paul and His Critics","author":"Enoch Hale","content":"<p><img style=\"float: right;\" src=\"https://www.criticalthinking.org/image/pimage/P1010077.jpg\" alt=\"\" /><span><span style=\"color: #000080;\"><strong>Clarifying the Discourse on Critical Thinking: Where and How Paul Provides the Framework for a Trans-Disciplinary Conceptualization:</strong></span><br /> It is widely agreed that the discourse on critical thinking is fragmented. Although common conceptualizations can be found in the numerous definitions of critical thinking, this base-line is often abandoned in lieu of discipline specific conceptualizations that do little to challenge the status quo both in departmental traditions and in its applications within education. Since critical thinking provides the tools for analyzing and assessing thinking within every subject and discipline, and thus without these tools, no subjects or disciplines can exist, it follows that critical thinking must be placed at the heart of the curriculum within and across the disciplines. Paul has developed a trans-disciplinary approach to critical thinking that explicitly illuminates the link between critical thinking and thinking within the disciplines.&nbsp;He has shaped a concept of critical thinking with substance and vision, applicable to every domain of human thought.</span><br /> <br /> <span>This session will examine Paul's work in relation to the rather fragmented discourse on critical thinking. It will outline Paul's mission and critics, and it will critique the different ways scholars have constructed discipline specific conceptualizations of critical thinking. The purpose, then, is to clarify the discourse and Paul's place within it for those interested in the theory of critical thinking.<br /> </span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Points of View, Frames of Reference, and World Views That Foster Open-mindedness

To understand our experience and the world itself, we must be able to think within alternative world views. We must question our ideas. Ideas are to us like the air we breathe. We project them everywhere. Yet we rarely notice this. We use ideas to create our way of seeing things. What we experience we experience through ideas, often funneled into the categories of “good” and “evil.” We assume ourselves to be good. We assume our enemies to be evil. To the uncritical mind, it is as if people in the world came to us with our labels for them inherent in who they are. THEY are “terrorists.” WE are “freedom fighters.” All of us fall victims at times to an inevitable illusion of objectivity. Thus we see others not as like us in a common human nature, but as “friends” and “enemies,” and accordingly “good” or “bad.” Ideology, self-deception, and myth play a large part in our identity and how we think and judge. We apply ideas, however, as if we were simply neutral observers of reality. We often become self-righteous when challenged. If we want our students to develop as learners, they must come to recognize the ideas through which they see and experience the world. They must take explicit command of their thinking. They must become the master of their own ideas. They must learn how to think with alternative ideas, alternative “world views.” This think tank lays the foundation for this process.

{"id":489,"title":"Points of View, Frames of Reference, and World Views That Foster Open-mindedness","author":"Richard Paul","content":"<p>To understand our experience and the world itself, we must be able to think within alternative world views.&nbsp;We must question our ideas. Ideas are to us like the air we breathe.&nbsp;We project them everywhere.&nbsp;Yet we rarely notice this. We use ideas to create our way of seeing things. What we experience we experience through ideas, often funneled into the categories of &ldquo;good&rdquo; and &ldquo;evil.&rdquo; We assume ourselves to be good.&nbsp;We assume our enemies to be evil. To the uncritical mind, it is as if people in the world came to us with our labels for them inherent in who they are. THEY are &ldquo;terrorists.&rdquo; WE are &ldquo;freedom fighters.&rdquo; All of us fall victims at times to an inevitable illusion of objectivity. Thus we see others not as like us in a common human nature, but as &ldquo;friends&rdquo; and &ldquo;enemies,&rdquo; and accordingly &ldquo;good&rdquo; or &ldquo;bad.&rdquo; Ideology, self-deception, and myth play a large part in our identity and how we think and judge. We apply ideas, however, as if we were simply neutral observers of reality.&nbsp;We often become self-righteous when challenged. If we want our students to develop as learners, they must come to recognize the ideas through which they see and experience the world. They must take explicit command of their thinking. They must become the master of their own ideas. They must learn how to think with alternative ideas, alternative &ldquo;world views.&rdquo;&nbsp;This think tank lays the foundation for this process.<br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

The Role of Testing and Assessment in Intellectual Engagement

The purpose of assessment in instruction is improvement. The purpose of assessing instruction for critical thinking is improving the teaching of discipline-based thinking (historical, biological, sociological, mathematical thinking…). It is to improve students’ abilities to think their way through content, using disciplined skill in reasoning. The more particular we can be about what we want students to learn about critical thinking, the better can we devise instruction to serve that particular purpose.

Unfortunately, standardized tests now widely used in critical thinking are not designed to impact instruction. There is a significant disconnect between what standardized tests assess and what we want students to learn. In this session, we will introduce critical thinking assessment tools offered by the Foundation for Critical Thinking.

For our white paper on testing and assessment, click here https://www.criticalthinking.org/files/White%20PaperAssessmentSept2007.pdf

{"id":490,"title":"The Role of Testing and Assessment in Intellectual Engagement","author":"Gerald Nosich","content":"<p><span>The purpose of assessment in instruction is improvement. The purpose of assessing instruction for critical thinking is improving the teaching of discipline-based thinking (historical, biological, sociological, mathematical thinking&hellip;). It is to improve students&rsquo; abilities to think their way through content, using disciplined skill in reasoning. The more particular we can be about what we want students to learn about critical thinking, the better can we devise instruction to serve that particular purpose.</span><br /> <br /> <span>Unfortunately, standardized tests now widely used in critical thinking are not designed to impact instruction. There is a significant disconnect between what standardized tests assess and what we want students to learn.&nbsp;<span>In this session, we will introduce critical thinking assessment tools offered by the Foundation for Critical Thinking.<br /> <br /> </span></span>For our white paper on testing and assessment, click here <a href=\"/files/White%20PaperAssessmentSept2007.pdf\">https://www.criticalthinking.org/files/White%20PaperAssessmentSept2007.pdf</a><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

**Advanced Session: In Search of a History of Critical Thinking:

The Age of Industrialization (1850 to 1950)

Rush Cosgrove

Nationalism, Capitalism, Neo-Imperialism, Colonialism: Wars for Markets and Ideology, Factory Industrialism, Mass Man, Fascism, the Emergence of Mass Media, Mass Public Schooling, World Wars, The Roots of the Cold War, Relativity, the United Nations.

Some relevant thinkers: Newman, Mill, Darwin, Spencer, Marx, Freud, Fromm, Sumner, Gustavus Myers, Dewey, Sartre, Russell, Wittgenstein, Durkheim, Weber, George Herbert Mead, Piaget, Churchill, Simone de Beauvoir, Margaret Mead, Henry David Thoreau, Mencken, Einstein, Glaser

{"id":491,"title":"**Advanced Session: In Search of a History of Critical Thinking:","author":"","content":"<p><strong class=\"head\">The Age of Industrialization (1850 to 1950)</strong><span class=\"f2\"> <br /> &nbsp; <strong>Rush Cosgrove</strong> </span><br /> <span><span style=\"color: #000080;\"><strong>Nationalism, Capitalism, Neo-Imperialism, Colonialism:</strong></span> Wars for Markets and Ideology, Factory Industrialism, Mass Man, Fascism, the Emergence of Mass Media, Mass Public Schooling, World Wars, The Roots of the Cold War, Relativity, the United Nations.</span><br /> <br /> <span>Some relevant thinkers: Newman, Mill, Darwin, Spencer, Marx, Freud, Fromm, Sumner, Gustavus Myers, Dewey, Sartre, Russell, Wittgenstein, Durkheim, Weber, George Herbert Mead, Piaget, Churchill, Simone de Beauvoir, Margaret Mead, Henry David Thoreau, Mencken, Einstein, Glaser</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Day Four: Morning Choose from one of the following sessions:

{"id":492,"title":"","author":"","content":"<p><strong><span style=\"font-size: 16pt; color: blue;\">Day Four: Morning </span></strong><span style=\"color: blue;\"><em><span>Choose from one of the following sessions:</span></em></span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Sociocentric Thinking: Impediments to Intellectual Development

Many of the most deep seated habits that humans acquire come from the process of being socialized or enculturated. Almost everything we think or do, we have been taught to think or do by the social groups that have shaped us. Those who want to free themselves from indoctrination, to become intellectually emancipated, must understand this problem as a significant barrier to their development and begin to see its influence on their daily thinking.

Many of the most deep seated habits that humans acquire come from the process of being socialized or enculturated. Almost everything we think or do, we have been taught to think or do by the social groups that have shaped us. Those who want to free themselves from indoctrination, to become intellectually emancipated, must understand this problem as a significant barrier to their development and begin to see its influence on their daily thinking.

Living a human life entails membership in a variety of human groups. This typically includes groups such as nation, culture, profession, religion, family, and peer group. We find ourselves participating in groups before we are aware of ourselves as living beings. We find ourselves in groups in virtually every setting in which we function as persons. What is more, every group to which we belong has some social definition of itself and some usually unspoken “rules” that guide the behavior of all members. Each group to which we belong imposes some level of conformity on us as a condition of acceptance. This includes a set of beliefs, behaviors, and taboos.

For most people, blind conformity to group restrictions is automatic and unreflective. Most effortlessly conform without recognizing their conformity. They internalize group norms and beliefs, take on the group identity, and act as they are expected to act—without the least sense that what they are doing might reasonably be questioned. Most people function in social groups as unreflective participants in a range of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors analogous, in the structures to which they conform, to those of urban street gangs.

This conformity of thought, emotion, and action is not restricted to the masses, or the lowly, or the poor. It is characteristic of people in general, independent of their role in society, independent of status and prestige, independent of years of schooling. It is in all likelihood as true of college professors and their presidents as students and custodians, as true of senators and chief executives as it is of construction and assembly-line workers. Conformity of thought and behavior is the rule in humans, independence the rare exception.

This session will focus, then, on the problem of sociocentric thinking in human life, and its implications for living a rational life, as well as for teaching and learning.

{"id":493,"title":"Sociocentric Thinking: Impediments to Intellectual Development","author":"Linda Elder","content":"<p><img id=\"__mce\" style=\"float: right;\" src=\"https://www.criticalthinking.org/image/pimage/P1010082.jpg\" alt=\"\" /><span>Many of the most deep seated habits that humans acquire come from the process of being socialized or enculturated.&nbsp;Almost everything we think or do, we have been taught to think or do by the social groups that have shaped us. Those who want to free themselves from indoctrination, to become intellectually emancipated, must understand this problem as a significant barrier to their development and begin to see its influence on their daily thinking.</span></p>\r\n<p><span>Living a human life entails membership in a variety of human groups. This typically includes groups such as nation, culture, profession, religion, family, and peer group. We find ourselves participating in groups before we are aware of ourselves as living beings. We find ourselves in groups in virtually every setting in which we function as persons. What is more, every group to which we belong has some social definition of itself and some usually unspoken &ldquo;rules&rdquo; that guide the behavior of all members. Each group to which we belong imposes some level of conformity on us as a condition of acceptance. This includes a set of beliefs, behaviors, and taboos.</span></p>\r\n<p>For most people, blind conformity to group restrictions is automatic and unreflective. Most effortlessly conform without recognizing their conformity. They internalize group norms and beliefs, take on the group identity, and act as they are expected to act&mdash;without the least sense that what they are doing might reasonably be questioned. Most people function in social groups as unreflective participants in a range of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors analogous, in the structures to which they conform, to those of urban street gangs.</p>\r\n<p>This conformity of thought, emotion, and action is not restricted to the masses, or the lowly, or the poor. It is characteristic of people in general, independent of their role in society, independent of status and prestige, independent of years of schooling. It is in all likelihood as true of college professors and their presidents as students and custodians, as true of senators and chief executives as it is of construction and assembly-line workers. Conformity of thought and behavior is the rule in humans, independence the rare exception.</p>\r\n<p>This session will focus, then, on the problem of sociocentric thinking in human life, and its implications for living a rational life, as well as for teaching and learning.<br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Teaching Students to Assess Their Own Work and That of Their Peers

Good thinking is thinking that (effectively) assesses itself. Critical thinkers do not simply state the problem; they assess the clarity of their own statements. They do not simply gather information; they check it for its relevance and significance. They do not simply form an interpretation; they check to make sure their interpretation has adequate evidentiary support. Because of the importance of self-assessment to critical thinking, it is important to bring it into the structural design of every course and not just leave it to random or chance use. This session will focus on how to help students give constructive feedback that helps others as they expand their knowledge and insight by getting constructive feedback from those others. By this means, students can learn how to help other students think more clearly, accurately, precisely, relevantly, deeply, broadly, logically, and fairly (as they learn how to do so themselves).

{"id":494,"title":"Teaching Students to Assess Their Own Work and That of Their Peers","author":"Richard Paul","content":"<p><span>Good thinking is thinking that (effectively) assesses itself. Critical thinkers do not simply state the problem; they assess the clarity of their own statements. They do not simply gather information; they check it for its relevance and significance. They do not simply form an interpretation; they check to make sure their interpretation has adequate evidentiary support. Because of the importance of self-assessment to critical thinking, it is important to bring it into the structural design of every course and not just leave it to random or chance use. This session will focus on how to help students give constructive feedback that helps others as they expand their knowledge and insight by getting constructive feedback from those others.&nbsp;By this means, students can learn how to help other students think more clearly, accurately, precisely, relevantly, deeply, broadly, logically, and fairly (as they learn how to do so themselves).</span><br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Critical Thinking Competency Standards: Keys to Intellectual Engagement

Much lip service is given to the notion that students are learning to think critically. A cursory examination of critical thinking competency standards (enumerated and elaborated in this session) should persuade any reasonable person familiar with schooling today that they are not.

Much lip service is given to the notion that students are learning to think critically. A cursory examination of critical thinking competency standards (enumerated and elaborated in this session) should persuade any reasonable person familiar with schooling today that they are not.

Critical thinking competency standards, which are the focus of this session, serve as a resource for teachers, curriculum designers, administrators and accrediting bodies. The use of these competencies across the curriculum will ensure that critical thinking is fostered in the teaching of any subject to all students at every grade level. These competency standards can be found in A Guide for Educators to Critical Thinking Competency Standards: Standards, Principles, Performance Indicators, and Outcomes With a Critical Thinking Master Rubric, which will be provided to all conference participants and will be used throughout this session.

This guide, Critical Thinking Competency Standards, provides a framework for assessing students’’ critical thinking abilities. It enables administrators, teachers and faculty at all levels (from elementary through higher education) to determine the extent to which students are reasoning critically within any subject or discipline. These standards include outcome measures useful for teacher assessment, self-assessment, as well as accreditation documentation. These competencies not only provide a continuum of student expectations, but can be contextualized for any academic subject or domain and for any grade level. In short, these standards include indicators for identifying the extent to which students are using critical thinking as the primary tool for learning.

By internalizing the competencies, students will become more self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored thinkers. They will develop their ability to:

- raise vital questions and problems (formulating them clearly and precisely);

- gather and assess relevant information (using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively and fairly);

- come to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions (testing them against relevant criteria and standards);

- think open-mindedly within alternative systems of thought (recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, implications, and practical consequences); and

- communicate effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems.

In this session, participants will work their way through many of the critical thinking competency standards. Participants will think through how these standards can and should be applied to teaching, learning and assessment in their subject or discipline, in their school or college.

{"id":495,"title":"Critical Thinking Competency Standards: Keys to Intellectual Engagement","author":"Gerald Nosich","content":"<p><img id=\"__mce\" style=\"float: right;\" src=\"https://www.criticalthinking.org/image/pimage/P1010007.jpg\" alt=\"\" /><span>Much lip service is given to the notion that students are learning to think critically. A cursory examination of critical thinking competency standards (enumerated and elaborated in this session) should persuade any reasonable person familiar with schooling today that they are not. </span></p>\r\n<p><span>Critical thinking competency standards, which are the focus of this session, serve as a resource for teachers, curriculum designers, administrators and accrediting bodies. The use of these competencies across the curriculum will ensure that critical thinking is fostered in the teaching of any subject to all students at every grade level. These competency standards can be found in <em>A Guide for Educators to Critical Thinking Competency Standards</em>: <em>Standards, Principles, Performance Indicators, and Outcomes With a Critical Thinking Master Rubric</em>, which will be provided to all conference participants and will be used throughout this session. </span></p>\r\n<p><span>This guide, <em>Critical Thinking Competency Standards</em>, provides a framework for assessing students&rsquo;&rsquo; critical thinking abilities. It enables administrators, teachers and faculty at all levels (from elementary through higher education) to determine the extent to which students are reasoning critically within any subject or discipline. These standards include outcome measures useful for teacher assessment, self-assessment, as well as accreditation documentation. These competencies not only provide a continuum of student expectations, but can be contextualized for any academic subject or domain and for any grade level. In short, these standards include indicators for identifying the extent to which students are using critical thinking as the primary tool for learning. </span></p>\r\n<p><span>By internalizing the competencies, students will become more self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored thinkers. They will develop their ability to:</span></p>\r\n<ul type=\"disc\">\r\n<li><span>raise vital questions and problems (formulating them clearly and precisely); </span></li>\r\n<li><span>gather and assess relevant information (using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively and fairly); </span></li>\r\n<li><span>come to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions (testing them against relevant criteria and standards); </span></li>\r\n<li><span>think open-mindedly within alternative systems of thought (recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, implications, and practical consequences); and </span></li>\r\n<li><span>communicate effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems. </span></li>\r\n</ul>\r\n<p>In this session, participants will work their way through many of the critical thinking competency standards. Participants will think through how these standards can and should be applied to teaching, learning and assessment in their subject or discipline, in their school or college.<br style=\"clear: both;\" /></p>","public_access":"1","public_downloads":"1","sku":"","files":{},"images":{}}

Fostering Intellectual Engagement Through Critical Writing